Among the most aspired Sustainable Development Goals for indigenous peoples is SDG 10 on reducing inequality within and among countries. SDG 10 as set by the United Nations states that countries “By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status.”

The UN has defined 10 targets and 11 indicators to track the achievement of countries on reducing inequality. This article looks into the performance of the Philippine State with respect to Indicator 10.3.1 on eliminating discriminatory practices.

SDG Indicator 10.3.1 sets the goal to “Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices by 2030.” An indicator in measuring compliance is “the proportion of population reporting having personally felt discriminated against or harassed in the previous 12 months on the basis of a ground of discrimination prohibited under international human rights law.” The global indicator covers all forms of discrimination prohibited under international human rights laws, starting from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the subsequent international human rights instruments.

To track the proportion of population having personally felt discriminated against or harassed is through survey ensuring representative sample and data reliability. Despite its limited and narrow coverage as measurement for discrimination, the SDG-tracker reported that no data is available on this indicator from any country. In other words, no country is doing a survey to get the proportion of persons that have felt discriminated against or harassed.

Let us look into widely reported cases of discrimination felt by Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines.

Lumad children and youth deprived of right to self-determined education

Photo credit: Save Our Schools Network

At least 3,500 Lumad children and youth felt discriminated against in regard to their right to self-determined and culturally appropriate education when the Department of Education (DepEd) closed or denied renewal of permit to 55 Lumad-managed and earlier accredited schools. At least 100 Lumad children and youth were similarly discriminated against when the Alternative Learning Center for Agricultural and Livelihood and Development (ALCADEV) and Mindanao Inter Faith Services Foundation (MISFI) were forced to close down in mid-2020 due to persistent attacks by government armed forces units and their paramilitary groups.

A police and Social Welfare Development local office forcibly took 19 Lumad youth studying in a Lumad Bakwit School (Lumad Evacuee School) in Cebu, Central Visayas. Two teachers, two datu (chief) and three students were arrested, charged and detained for more than a year for serious illegal detention of these Lumad youth. They were released only recently when a court dismissed their cases. The Lumads, who were about to complete their modular studies in April 2020 and return to their families after, were being sheltered by the SVD Roman Catholic community as they were locked down by the COVID-19 restrictions.

All these discriminatory actions are rooted in the State’s targeted attacks against indigenous peoples and their schools that it claims are strongholds of the Communist Party of the Philippines, New People’s Army (NPA) and National Democratic Front of the Philippines.

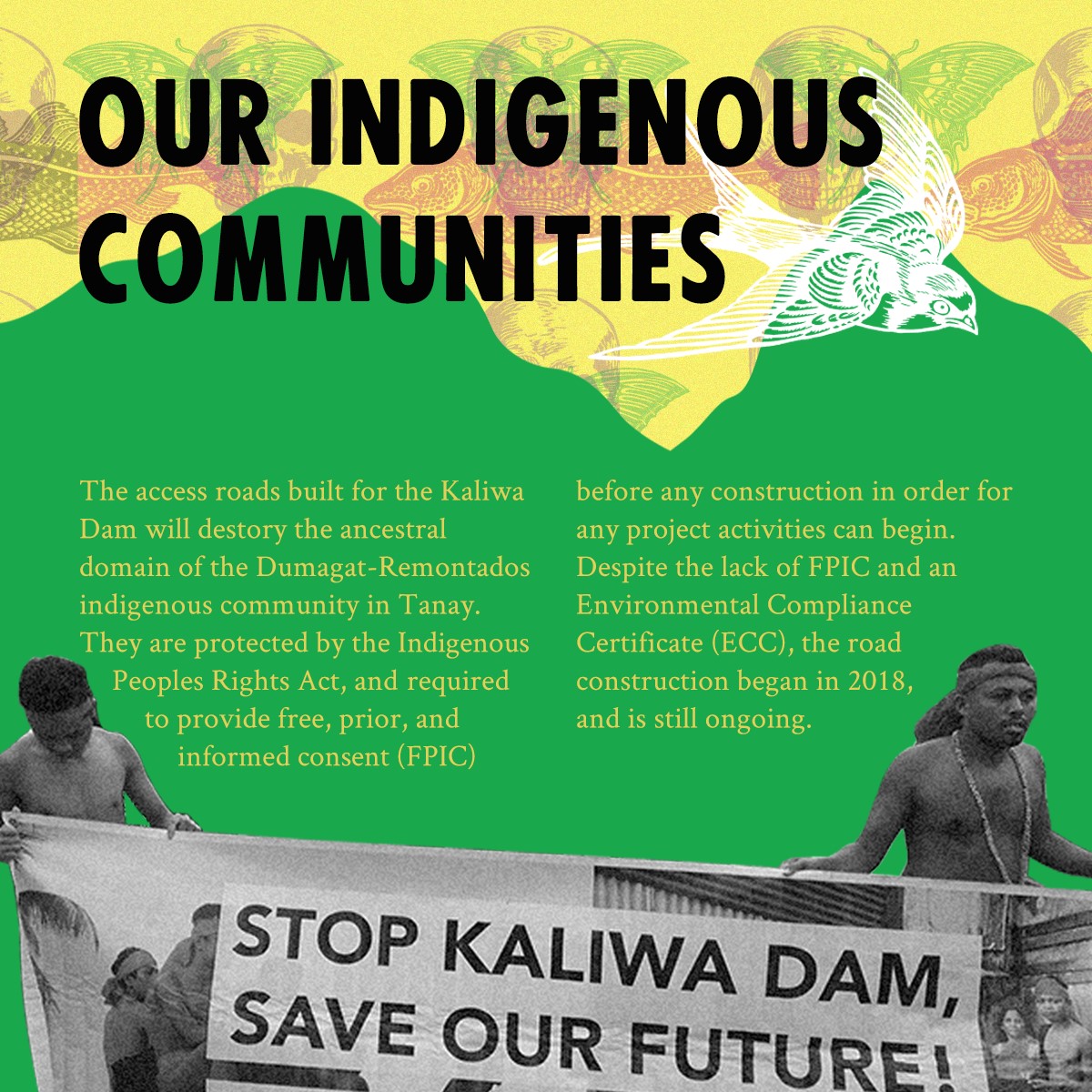

Dumagat-Remontado to be displaced for national capital’s water security

Photo credit: Stop Kaliwa Dam

An estimated 31,000 Dumagat-Remontado (Panaghiusa, Case Digest in the Philippines) of the Sierra Madre Mountain in Rizal and Quezon provinces have long been saying they will be disenfranchised from their ancestral homeland in favor of securing water for the national capital region. The New Centennial Water Source Project – Kaliwa Dam will inundate almost 300 hectares of Dumagat-Remontado land, which became part of the Reina Natural Park, Wildlife Sanctuary and Gaming Preserve under a Presidential Decree of former President Ferdinand Marcos. A flagship project under the Duterte administration’s Build, Build, Build program, the P12 billion project will be constructed by China Energy Engineering Corporation and funded mostly by an Export-Import Bank of China loan which some quarters deem as “financially disadvantageous” to the country.

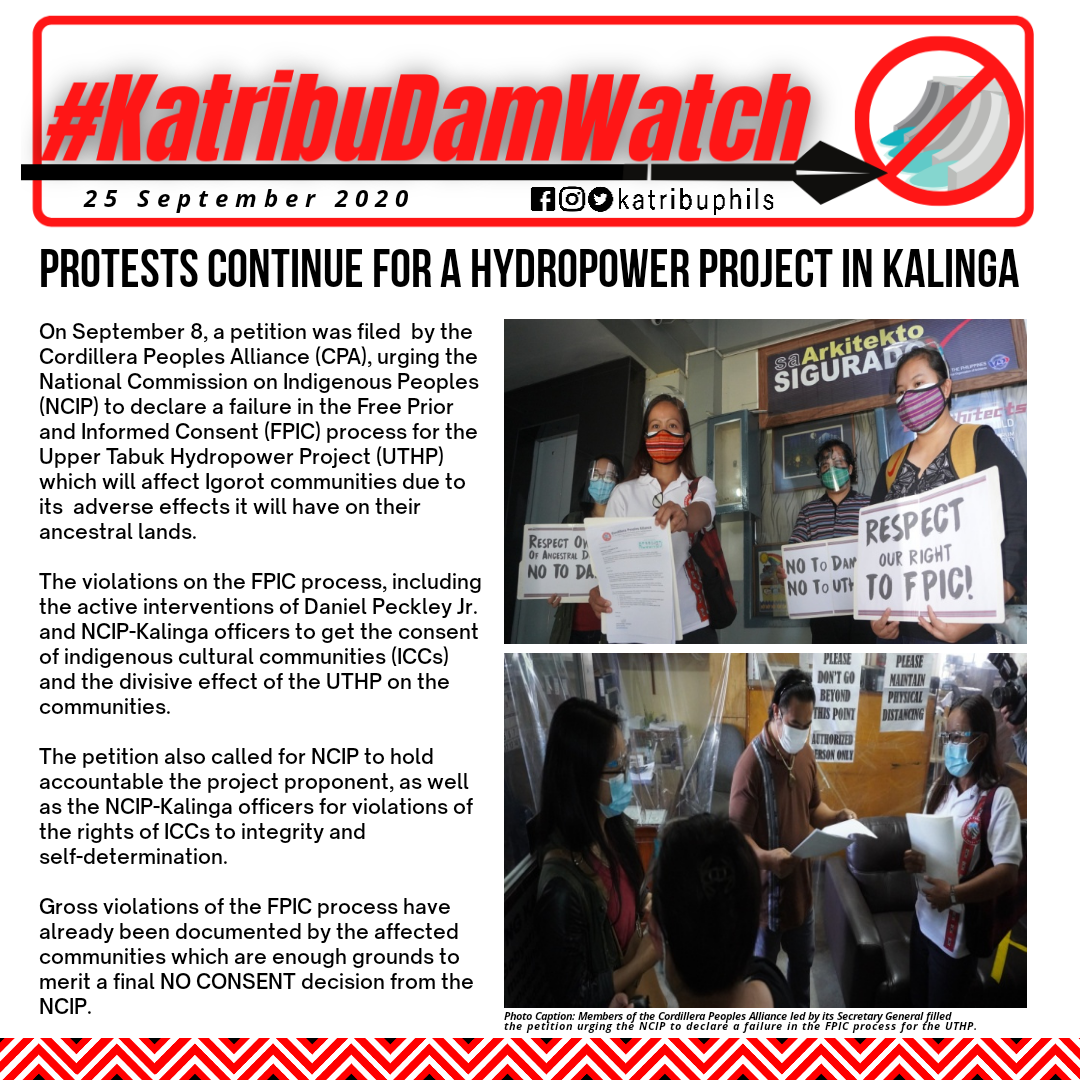

Kalinga tribe replaced by “new tribe” in FPIC process for hydropower project

Photo credit: Katribu Kalipunan ng Katutubong Mamamayan ng Pilipinas

A Kalinga tribe has felt betrayed by a hydropower company for having created a “new tribe- Minanga tribe” that signed the Memorandum of Agreement as the final stage in securing the Certification Precondition under the Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) process for the 15 mw-Upper Tabuk Hydropower project. Two hundred petitioners have contested the MOA and disowned the created tribe.

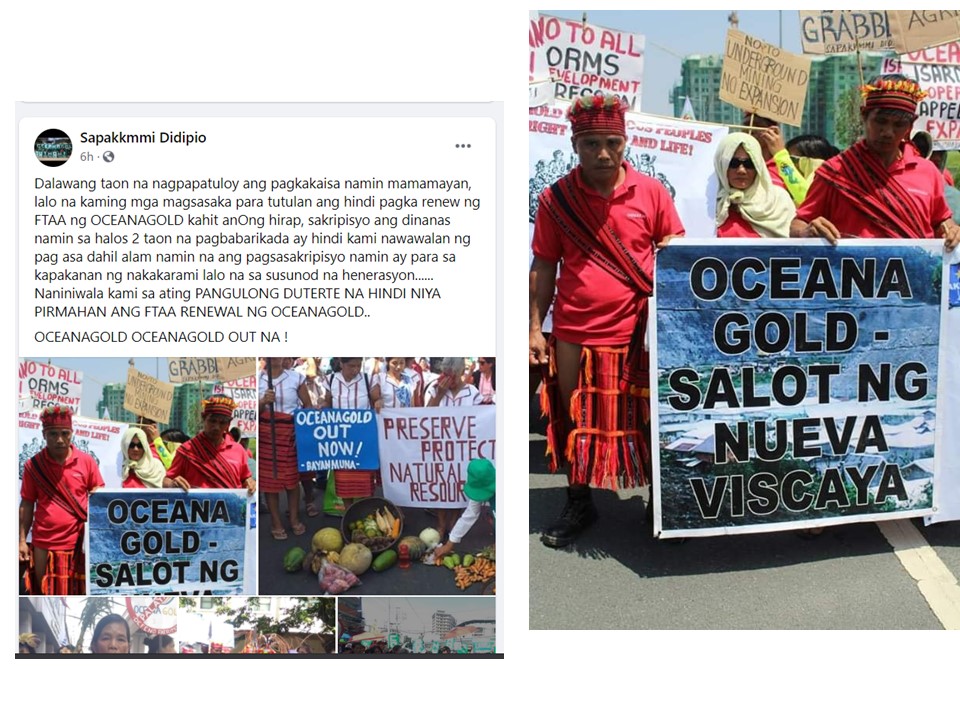

Ifugaos affected by Oceana Gold Philippines

Photo credit: Sapakkmmi Didipio

Fifteen leaders and members of the Didipio Earth Savers Movement Association (DESAMA) were charged with violating the Law on Reporting of Communicable Diseases. Those arrested were barricading the entry and exit point of Oceana Gold’s gold and copper mine in Nueva Vizcaya after it was issued a cease-and-desist order by the Provincial Government on the ground that its 25-year Financial and Technical Agreement had expired. DESAMA has been protesting the company’s operations which has affected Ifugao communities and lands.

Extrajudicial killings of Tumandoks affected by Jalaur Dam

Photo credit: Sabokahan Unity of Lumad Women

Nine Tumandoks were killed in a police operation in Iloilo and Capiz provinces claimed by State security forces to be NPA members who fought back when served warrants of arrest. Another 16 Tumandoks were arrested and charged with illegal possession of explosives and firearms. These Tumandoks had long been seeking effective participation in negotiations on matters of dislocation and subsequent relocation and livelihood in relation to the Jalaur dam project (Business Mirror, Sept. 4, 2014). The Php11.2B Jalaur dam is a 109-meter high impounding dam for multipurpose irrigation of 32,000 hectares of largely rice land in lowland areas of Western Visayas (Katuwang sa Kauswagan, April 23, 2021).

Potentially discriminatory laws and administrative policies

The most threatening for the security and liberty of Indigenous Peoples is the Anti Terrorism Act viewed as an affront to the right to self-determination, in addition to being overly broad and vague. Opposition to large energy and mining projects in indigenous territories could be construed as an act of terrorism. The first two victims now incarcerated and facing charges of violation of the law are two indigenous Aetas.

The Executive Order No. 130 issued by President Rodrigo Duterte in April 2021 lifted the 9-year ban on mineral agreements in protected areas issued by his predecessor in 2012. Widely affected by the EO will be Indigenous Peoples who are inhabiting and stewarding these mineral lands and depend on these for their survival. Earlier in 2018, a law was enforced easing the systems and procedures in securing business requirements from local and government agencies (Republic Act 11032). Again, for Indigenous Peoples this law will overturn whatever affirmative gains have been established in the processes of securing Free, Prior and Informed Consent.

Various administrative and regulatory mechanisms set by various government agencies in relation to Civil Society Organizations (CSO)/People’s Organizations (POs) are also restrictive and repressive. These are discriminatory for Indigenous Peoples whose POs are organized in the customary practice and with track records of opposing large scale projects in their ancestral domains. Indigenous peoples’ organizations typically have no constitution and by-laws nor are their leaders and members formally defined. Organizations of Indigenous Peoples that remain uncompromising in claiming ancestral land rights and demanding accountability could be categorized by the government agencies as high risk and denied recognition or accreditation

Recommendations on indicators on reducing inequality in relation to Indigenous Peoples

Data disaggregation has long been raised by Indigenous Peoples as the first step towards addressing inequality on the basis of being indigenous peoples. Quantitative mapping of inequality can hardly be understood and addressed if data aggregation remains scarce and ignored.

Notwithstanding the absence of data disaggregation and the narrow yet complex and costly survey on felt discrimination, measuring inequality in relation to Indigenous Peoples can be achieved using indicators accepted widely by Indigenous Peoples and in a less complex and costly manner. For Indigenous Peoples, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) constitutes the minimum standard in setting goals and indicators in measuring inequality and discrimination against them. Achieving all the SDG goals as these apply to Indigenous Peoples should be tracked against the rights and well-being set forth in the Declaration. All 46 articles of the UNDRIP comprehensively articulate the targets and indicators in eliminating discrimination against and achieving equality for Indigenous Peoples.

For instance, goals, targets and indicators on discrimination should be aligned with Article 10 of UNDRIP which bans forcible removal of Indigenous Peoples from their territories, unless relocation with fair and just compensation is agreed and consented to freely. Article 14 sets the rights of Indigenous Peoples to establish their own education system consistent with their culture. Several articles are set on the right to “own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources that they possess by reason of traditional ownership or other traditional occupation or used, as well as those which they have otherwise acquired.”

Further, the UNDRIP details sets of obligation by the States “to take effective measures of redress, fair and just compensation and in a process that is fair, impartial, transparent and decided and conducted in conjunction with Indigenous Peoples.”

There is no need to engage in an expensive method of representative survey to generate data on felt discrimination by Indigenous Peoples. Several cases have been documented and publicly reported as illustrated in the above cited cases.

Data on persons experiencing discrimination can be consolidated from complaints officially logged and publicly decried. Effective measures taken by States in conjunction with Indigenous Peoples can also be quantified with the population that have been granted redress.

The Philippines is signatory to the landmark Declaration. It is thus reasonable and lawful to use the UNDRIP to gauge the progress or regress in achieving the targets and indicators on eliminating inequality and discrimination against Indigenous Peoples by the Philippine State.

Taking off from the cited cases of Indigenous Peoples having felt discrimination and others killed and incarcerated, these can be consolidated as indicators in quantifying discrimination. In the cited cases, it can safely be said that discrimination is pervasive for at least 34,859 indigenous individuals in the Philippines.

~Rhoda Dalang