“Any successful strategy to address socio-economic disparities in health will need to be based on a recognition that the highest threat to health inequity is overall social inequity.”

Cordillera Health Situation

In Malibcong, Abra, road going to the hospital is 5 hours through unpaved road.

A defining feature of the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) is that it is a contiguous 1.8 million-hectare territory of 7 major groups of Indigenous Peoples. It is the only region in the Philippines whose majority population are Indigenous Peoples. Composed of 6 provinces and one urbanized chartered city, CAR has a population of 1,797,660 (2020 census). The most populated is the province of Benguet with 460,683 and the least is Apayao with 124,366. Urban Baguio City’s population is 366,358.

Compared to other groups of Indigenous Peoples in the country, those in CAR share a higher level of health system as seen from the government’s 2020 Field Health Services Information System (FHSIS) on health facilities and personnel:

| Category | Target/Ideal Ratio | Regional Data | Range Across Provinces |

| Health center (rural, municipal and district) | 1:20,000 | 1:36,795 in Benguet to 1:9,163 in Abra | |

| Barangay health station | 1:5,000 | 1:3,086 in Benguet to 1:1,211 in Ifugao | |

| Doctor | 1:20,000 | 1:16,434 | 1:29,896 in Benguet to 1:9,896 in Abra |

| Nurse | 1:10,000 | 1:2,274 | 1:3,466 in Benguet to 1:1,567 in Abra.

|

| Midwife | 1:5,000 | 1:2,237 | 1:8,815 in Baguio City to 1:1,309 in Ifugao |

Except for health center and doctor ratios in the province of Benguet, the aggregate data indicate that the public health facilities and health workers in the region are within the ideal or targeted ratio based on the standards set by the government. However, given CAR’s widely dispersed communities in mountainous and steep terrain, access to these health services remains difficult for communities in geographically far flung areas. And while there are barangay health workers in these areas, they serve a widely dispersed cluster of small populations attached to the more populous center of the barangay, the basic local government unit. This is a special feature of people living in mountainous areas like Lacub in Abra, which thus need a more contextualized health system. In addition, the so-called barangay health stations are not supplied with basic health facilities.

The government’s aggregate data on ratio of health centers, doctors, nurses, midwives to population is less relevant for Indigenous Peoples living in isolated and hard-to-reach villages.

In like manner, regional aggregate health statistics from the FHSIS may not reflect the actual situation in far flung villages.

Health indices reflected in the 2020 FHSIS indicate that the Cordillera region is on track in achieving national objectives as well as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) targets in (a) maternal mortality ratio (b) infant mortality rate (d) prevalence of stunting among under-five children (e) incidence of low birth weight and other categories. On the other hand, deficiency in achieving targets was registered in three indicators: (a) percentage of fully immunized children (b) percentage of provinces that are malaria free (c) proportion of households using safely managed drinking water services. An overview of the health indices is presented in the following table:

| INDICATOR | SDG TARGET | NATIONAL TARGET | CORDILLERA | REMARKS |

| Maternal mortality ratio | 70/100,000 livebirths | 90/100,000 livebirths | 64.74 | Kalinga registered a high incidence at 216.45 and Benguet the lowest at 20 |

| Infant mortality rate | 17/1,000 livebirths | 17/1,000 livebirths | 8.8 | Highest rate in Baguio (13.67) and Mountain Province (12.75) and lowest in Abra at 3.26 |

| Under-five mortality rate | 25/1,000 livebirths | 25/1,000 livebirths | 10.51/1,000 livebirths | Baguio and Mountain Province had highest? indices at 16.37 and 15.59 respectively while Abra registered the lowest at 3.59 |

| low birth weight | S | 15/1,000 | 6.81/1,000 | Baguio (8.93) and Apayao (8.37) are highest and Ifugao lowest (3.68) |

| prevalence of stunting among under-five children | 26.7% | 7.36% | Stunting rates in Apayao, Abra, Kalinga and Mountain Province range from 11.58-12.67 and in Baguio, 1.75 | |

| Percentage of fully immunized children | 95% | 67.91% | Kalinga (92.53%) is highest and Baguio (50.22%) lowest | |

| Proportion of households using basic safe water | 95% | 82.1 | Only Abra (63.85) and Benguet (67.3) are below the regional average while the rest are above average ranging from 83.5 (Baguio) to 106.49 (Kalinga) | |

| Proportion of households using safely managed drinking water services | 60% | 54.35% | Kalinga (80.29) and Baguio (71.82) surpass the target while only 4.27% are using safely managed drinking water in Apayao |

The data indicate that a wide disparity in basic health condition exists among the provinces, which implies a similarly wide disparity when data is aggregated between provincial centers, town centers and far flung communities. Also noted was a seeming lack of correspondence in the indicators. For instance, urban Baguio City has the highest ratio of low birth weight but has the lowest prevalence of stunting in under-five children. While Baguio City has the highest standards of health system and drinking water system in the region, it is recorded as the least performer in major child health indicators: infant mortality, under-five mortality and low birth weight.

For Indigenous Peoples living in isolated villages, realization of the equal right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health would mean to engage a health system that is contextually accessible and affordable, respectful and supportive of traditional health-related practices and respects the right of Indigenous Peoples to freely engage in a human rights-based approach to health such as Community-Based Health Program.

People’s Struggle for Right to Health: The Community-Based Health Program

Preparing herbal medicine

In order to contribute in improving the health situation in the Philippines, efforts to build Community-Based Health Programs (CBHP) all over the country began in the 1970s. The CBHP is a people-managed primary health care system at the community level, where through genuine health education the community people are empowered to take health into their hands and chart their destiny through organized and concerted action.

Preparing Herbal Medicine

At the core of CBHP building is the education and training of community health volunteers (CHVs) who are members of people’s organizations. Community Health Volunteers’ training focuses on a holistic view of health (including the political, economic and social determinants of health), disease prevention (primarily sanitation and nutrition), diagnosis of diseases commonly found in the community and promotion, enhancement and introduction of traditional forms of treatment (home remedies, herbal medicine, acupuncture). The utilization of traditional therapeutic practices and use of medicinal plants is also promoted. These traditional therapeutic practices are accessible, affordable and more importantly, foster self reliance.

Acupuncture

CHVs are also taught to recognize and refer cases needing higher levels of care such as hospitalization.

Activities of the CHVs center on health campaigns to address priority health problems. Lectures on health (or health education) are given by the CHVs to their fellow community members as part of the effort to mobilize them towards improving their health conditions. Health campaigns commonly center on sanitation campaigns to build toilets and ensure proper disposal of animal waste. Another popular health campaign is medicinal plant propagation and preservation.

The institutionalization of the CBHP is integrated as a function of the Health Committee of the People’s Organizations (POs). This mechanism ensures that health organizing is integrated in the overall efforts of community empowerment.

In the Cordillera region, the Community-Based Health Program was introduced in 1981 through the NGO Community Health Education Services and Training in the Cordillera Region or CHESTCORE. CHESTCORE has been working to build Community-Based Health Programs all over the Cordillera Region. Priority is given to the far-flung areas where government health services are most inaccessible.

Today, CHESTCORE is subsumed as the health program of the Center for Development Programs in the Cordillera. CDPC is a network of NGOs and People’s Organizations advocating for the right to self-determined development in the context of the Indigenous Peoples as well as non-indigenous populace in the Cordillera region.

The Lacub Community-Based Health Program

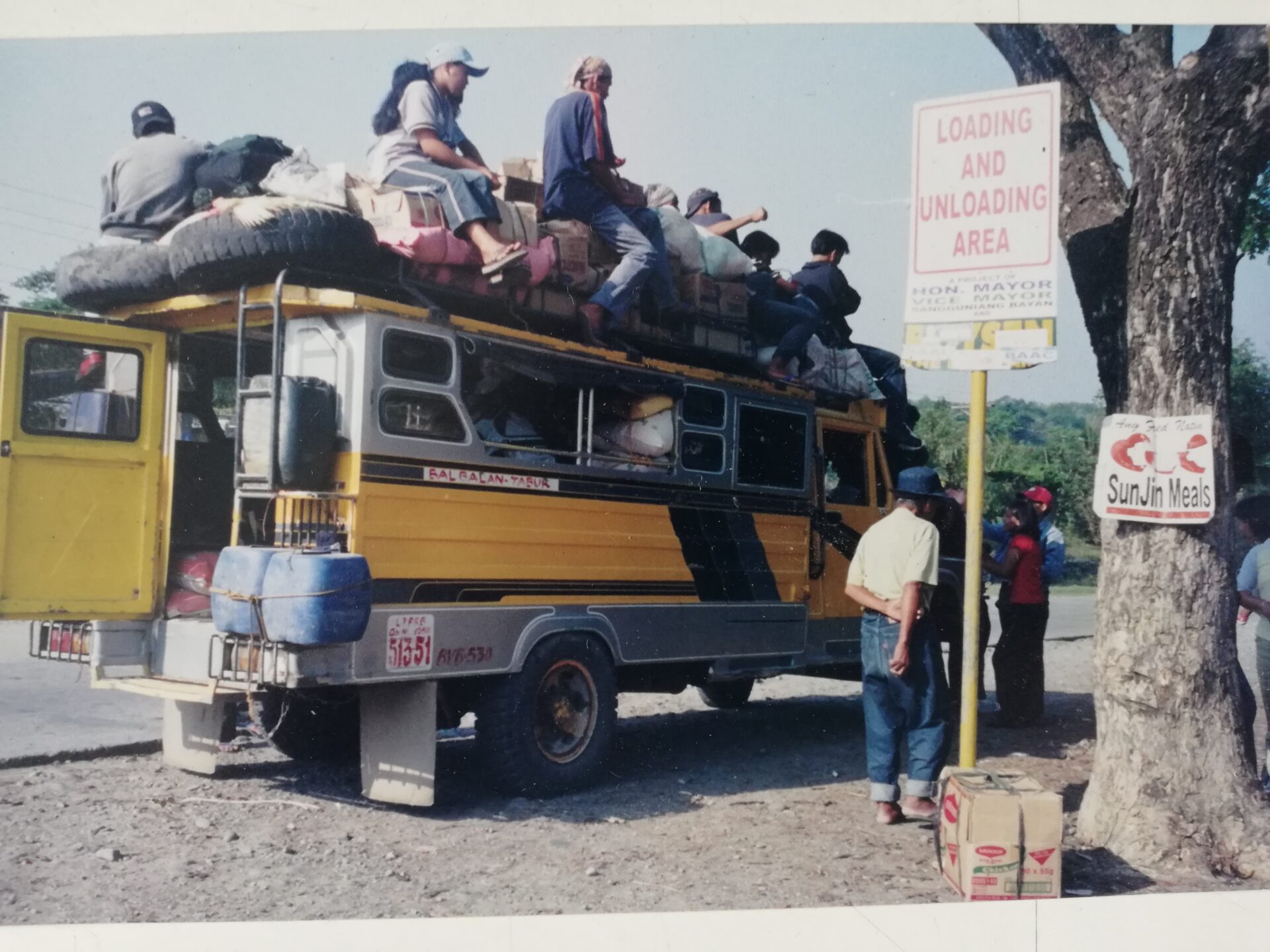

Lacub is a municipality located in the landlocked province of Abra. It has a land area of 235.53 sq kilometers comprising 5.61% of the province total area. Based on the 2020 Census, the mnicipality’s population was 3,612 representing 1.44% of the total population of the province. It is one of the more remote municipalities in the province. One has to endure a 5–7-hour jeepney ride through a recently paved road. Like other far flung areas in the Cordillera Region, the Indigenous Peoples of Lacub have limited access to basic services.

Jeepney ride going to Lacub

Lacub’s Community-Based Health Program, which started in 1987, is one of the oldest CHESTCORE has ever set up. At that time, 3 to 4 Community Health Volunteers from 4 barangays were given trainings on basic health care and later on advanced health care, minor surgery and dental care. From 1992-1996, a village health clinic was set up with the help of the Third World Relief Fund. Those who were trained maintained and manned the village health clinic with the supervision of a few CHESTCORE staff until the year 2000. Through the years, the CHVs were decentralized from an earlier municipal wide health clinic to the various sub-villages (barangays and sitios).

At the height of intensified militarization of Lacub and adjoining municipalities, and intense red-tagging of CHESTCORE, CHVs and POs, the CBHP was integrated into the local government health system through the hiring of the CHVs as barangay health workers (BHWs). Over time without the continuing skills training and logistical support from CHESTCORE, the roles and functions of the CHVs turned BHWs eventually narrowed down to service providers as health care providers. Also, the community health system is no longer community–managed. Engagement of communities in improving their health situation turned government-led.

CBHP as a Health Service System

By 2004, several of the CHVs trained in the 1980s to 1990s had retired due to old age, some migrated out of Lacub while others passed away. Given the need to train new CHVs, Lacub, together with the municipalities of Tubo and Malibcong, became priority areas for CBHP building from 2005-2012.

CHESTCORE conducted a Community Health Volunteers’ training in 2006 and 2007, which involved both new CHVs and those previously trained. They were trained in basic health care, maternal and child health, reproductive health, common diseases, pharmacology, acupuncture, dental health, mental health, history taking and physical examination, minor surgery and simple laboratory examinations.

The trainings were supported with a Community Clinic program which served as a form of practicum. This helped to boost the confidence of the CHVs and strengthened their commitment in serving sick community members. The community clinics were held in partnership with the government Rural Health Unit, the barangay officials, and members of the Friends of CHESTCORE (FOC) – the referral network of medical specialists maintained by CHESTCORE.

Because of its strong people’s organization and active health work, Lacub had been the site of several health campaigns and pilot health projects, such as the following:

- Interprovincial CHV Conference 2007

Lacub was host to the interprovincial CHV conference and training on basic life support in the rural setting, attended by CHVs from the provinces of Abra and Kalinga. The community health volunteers of Lacub displayed exemplary dedication for the preparation of the activity. The training gave extensive inputs on basic life support that equipped the CHVs with skills they could apply in cases of vehicular accidents or serious wounds. Advanced acupuncture, after care of the sick and mental health were also discussed. The activity also served as an opportunity for the CHVS from the 2 other provinces to share experiences and struggles.

- Mental Health Program 2009

It was also in Lacub that CHESTCORE piloted its mental health program. During the height of militarization, the POs requested for assistance in processing their experiences, especially the victims of human rights violations. CHESTCORE conducted psychosocial processing for the victims. A training on Mental Health in partnership with the government Rural Health Unit and the municipal government of Lacub was conducted. With the basic skills provided, the CHVs helped in facilitating the conduct of psychosocial processing for victims in their communities. The modern-day (Western) process of stress debriefing though was found not appropriate to the local culture and context, thus the traditional ways were explored and have since been interfaced in the mental health program of CHESTCORE and the CBHPs.

- Village Pharmacy 2009

With limited access to medicines, a village pharmacy was established in 2009. CHESTCORE facilitated the one-time provision of a set of basic medicines, which were distributed to the sub-villages of Lacub. The medicines were sold at a cheaper price, with the proceeds used to replenish their stock. A medical kit was also distributed. Both the medicines and the medical kit were placed under the care of the village health committees. Continuity support for this program was later subsumed by the municipal government through the Rural Health Unit.

An essential component of the Village Pharmacy was the continued promotion of medicinal plants. Apart from community production, herbal plants that are not endemic and hardly thrive in Lacub were supplemented by the herbal medicine production at CHESTCORE’s office maintained by volunteer medical students from the St. Louis University College of Medicine in Baguio.

- Community-Based Research 2006

A research on the health effects of small-scale mining was also conducted in the area. The research done in partnership with the UP Medical Foundation and Saint Louis University College of Medicine entailed interviews, physical examination of miners and case studies of the costs and benefits of mining. Volunteer medical students helped in the conduct of interviews, and a foreign engineer also participated in the research. As a result of the research, CHESTCORE subsequently conducted health education on occupational health and safety for indigenous small-scale miners.

The mobilization of volunteers from the health sector was an important component in the conduct of CHESTCORE’s work in Lacub from 2004-2012. Student Integration Programs and Community Integration Program for Physicians were designed to encourage students in various health fields, doctors, nurses and other health professionals to assist in the training of CHVs and support the conduct of their health campaigns. At the same time, these programs enabled students and health professionals to learn about the life conditions and issues faced by the villagers by living and working with them.

CBHP as a Human Rights-Based Approach to Health

In addition to being an avenue for primary health services, the CBHPs through the CHVs developed as lead actors in a human rights-based approach to health.

Campaign on sanitation. A continuing campaign of the CBHPs was community sanitation, which led to the construction of a community compost pit as part of the waste management campaign. Community sanitation also resulted in people fencing off their once freely roaming pigs.

Campaign against smoking. The campaign against smoking has been viewed as having contributed to fewer young adults engaged in smoking.

Campaign for nutritious food and herbal medicine production. Lacub was among the CBHP programs that had been producing Lagundi syrup for cough and garlic-chili-ginger ointments for rheumatism. The production sustained their community needs as well as those of adjoining villages. These herbal medicines were sold in the village pharmacy at production cost. The campaign for herbal medicine was complemented by by the campaign for backyard gardening of both herbal plants and vegetables. For additional source of vitamins and minerals, malunggay (Moringga) production was introduced, from planting to preservation through powdered and other various forms of consumption.

Campaign on disaster preparedness. Maintaining safe drinking water had been a continuing campaign through the use of running water and ensuring clean water source. The use of chlorine tablet was further introduced as part of measures to ensure potable water in times of typhoon and drought. And to ensure food supply in times of disasters, the main program centered on the management of the rice cooperative that makes rice, the food staple, available to those with limited supply.

Campaign for ensuring health safety in small scale mining activities. Small scale mining has been a recent supplemental livelihood of almost all households in Lacub. From the onset, the community has been dealing with a conflict on water with the observed decrease of irrigation water brought on my mining activities. To resolve the problem, the community adopted a resolution to comply with the customary law of “priority of first users,” a community reaffirmation to ensure irrigation water during the farming season and its use by small scale mining during off-season. In addition, a campaign was undertaken to refrain from using mercury in gold processing. Another campaign resulted in the planting of vegetables and medicinal herbs in mining camp sites.

Campaign for government health services. Lobbying for government support resulted in the acknowledgement and eventual integration by the Rural Health Unit of the community clinics/pharmacies. As a result of these lobbying efforts, sets of vital signs monitoring equipment were provided by politicians during electoral campaigns.

CBHP support to community campaigns. The CBHP supported the campaign on reinforcing the customary practice on natural resource management called Lapat. The Lapat sets regulations on hunting, harvesting of forest and river system products, swidden farming and other measures related to conservation and preservation of natural resources. The Lapat is among the customary strategies contributing to mitigating the impacts of climate change.

Human rights and ancestral land rights were among the continuing campaigns by the community that CBHP supported. The Lacub CHVs were among the active actors in the campaign against the persecution of CHVs, POs and CHESTCORE, both in their localities and in regional and national campaigns. They spearheaded a signature campaign to end the political persecution against them and to have the military detachment be removed from their ancestral territory.

From 2008 to 2010, attempts by corporate mining to operate in Lacub were opposed by the people due to foreseen destruction of the environment, livelihoods and social life. The people’s resistance was met with militarization. Troops of the Armed Forces of the Philippines encamped under the houses of residents and later established an encampment within the school compound. Human rights violations increased which included harassment, red-baiting, instilling fear, economic sabotage, sexual harassment and several cases of rape of minors. The soldiers did not respect existing community rules such as an alcohol ban. Some of them fired their firearms indiscriminately, scaring and endangering the lives of the people. The people resisted their presence in the community from the day they established their camp. The soldiers were forced to exit the community in 2010 due to this strong resistance. However, few years later, a military detachment was established right next to the Rural Health Center and the local elementary school.

Militarization affected all activities of the people’s organization, including those of the CHVs and the CBHP. Many were intimidated and community health activities were forced to slow down until the local government unit took over the program by hiring the community health volunteers and turning them into barangay health workers.

Community Health Volunteers integrated into Local Government Health System

Over the past decade, with the changes in local and national officials and the vicious political persecution and vehement red-tagging of CHESTCORE and the CHVs, the local government administration stopped the operations of all village pharmacies. Apparently, in order not to further enrage the villagers, the Local Government Unit employed the CHVs as barangay health workers.

Over time without the continuing skills training and logistical support from CHESTCORE, the roles and functions of the CHVs-turned-BHWs eventually narrowed down to service providers as health care providers. While they have maintained the interface of modern-day health care with indigenous and other traditional practices (i.e. acupuncture), their earlier role as promoters of the right to health deteriorated. Moreover, education and campaigns on the socio-political determinants on health died down. Subsequently, the Community Based Health Program regressed into a purely clinical program and became fully integrated in the government health system, although the instilled indigenous and other traditional health care systems remain sustained but only in cases where the BHWs are former CHVs. Moreover, the community health system is no longer community-managed. While community support prevails in times of health emergencies, the villagers have gradually become dependent on health care services from the BHWs and other government bodies. Community-led campaigns on elaborating health-related issues and engaging in community actions are no longer conducted. Engagement of communities in improving their health situation has become government-led.

Lessons Learned

Community-Based Health Program as joint engagement of NGOs and POs is still greatly needed in maintaining health resilience of underserved communities. This is especially relevant for indigenous communities whose arsenal of indigenous knowledge systems complement modern day scientific knowledge and is guided by the social values and practices on community volunteerism for community welfare.

Volunteerism and genuine service are the core values that the CHESTCORE-PO CBHP program has been reinforcing. Volunteerism and genuine service are the building blocks in building trust and confidence among the villagers to take their health program into their hands. This is where the CHESTCORE CBHP program has been making a contribution. The CBHP program has not only been contributing to developing skills of CHVs and the villagers as a whole. It has also been contributing to reinforcing indigenous social values and practices in community welfare which are vital in building community health resilience.

In addition, the CBHP core strategy built on a human rights-based approach grounded on community mobilization, action and ownership remains relevant, effective and efficient in building a community-based health service program.

It is unfortunate and irresponsible for the government to be persecuting the NGO-PO-managed CBHPs now that the world is grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic. Had the CBHPs not been persecuted and decimated, these could have contributed greatly in the information dissemination much needed in curbing the disinformation on COVID-19 and in dealing with community-based coping mechanisms.

PostScript:

Our greatest reward has always been seeing the transformation of barely-literate farmers used to silently enduring poverty and exploitation into empowered leaders and members of their peoples’ organizations and Health Committees. We bear witness that it IS possible to place “health in the hands of the people” through community-based health programs.